emmy·in·the·mix on a deep dive into Jerash Camp, the home of SEP

Posted on August 26 2021

Refugees from a land never seen: the case of Gaza (Jerash) Camp in Jordan

A Blog Post written and published by emmyinthemix.com.

For the original article and much more, click HERE.

There is a hill to climb to reach it. Remember that, because along the road, not a single sign hints at the presence of a camp, or rather of a city, a term closer to reality. The Gaza refugee camp exists without really existing. Its people live there without really belonging there. I wanted to understand why this is one of the poorest camps in Jordan. On a June afternoon, I had the chance to meet with a few residents* from the camp who answered my many questions, helping me understand what it’s like for them to be refugees, today.

Camp ID

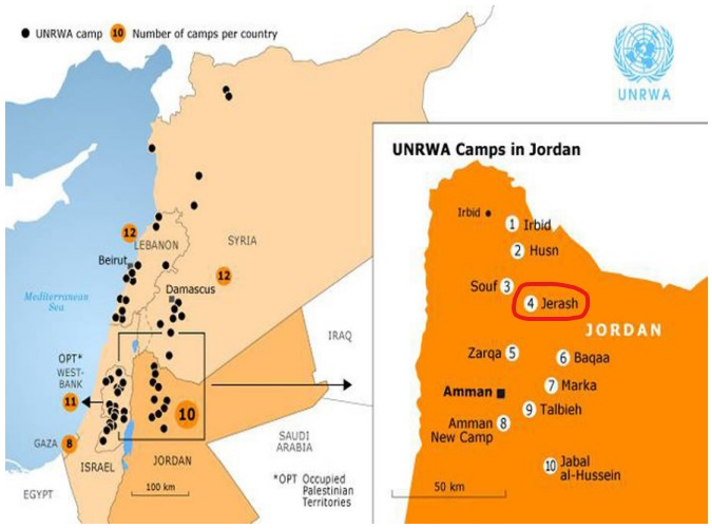

Located in Jerash, a city located in northern Jordan, the camp was set up in 1968 by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) as an “emergency” camp for 11,500 Palestine refugees and displaced persons who fled the Gaza Strip during the 1967 Arab-Israeli war. This is the reason why it is called the “Gaza” camp.

The land was leased by the Jordanian government to the UNRWA for a duration of 100 years. It covers an area of 0.75 square kilometres and it currently hosts over 40,000 refugees.

According to the UNRWA, the camp is the poorest among the 10 Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan, with 52.7% of its population earning an income below the national poverty line.

Map of UNRWA refugee camps with a focus on Jordan. Source: PRC 2018 report

Multiple forced displacement: a historical perspective

The 1948 and 1967 wars

To understand why these camps exist, we need to go back in time to two wars, which caused significant displacement.

In November 1947, the United Nations voted to partition the British mandate of Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state. The British had ruled over this territory for almost 30 years. This decision was both considered by the Jewish community in Palestine to be a legal basis for the establishment of Israel, and rejected by the Arab community. Clashes broke out between the two communities and escalated. In May 1948, on the eve of the British forces’ withdrawal, Israel declared independence. The next day, a coalition of Arab states invaded part of the territory to restore law and order, in light of massacres and a growing refugee crisis impacting Palestinians. By 1949, the Israelis occupied all of the Negev, except for the Gaza strip. This event is called the “War of Independence” by the Israelis and “the Nakba” (meaning catastrophe) in the Arab world because of the large number of refugees and displaced persons it caused: around 750,000.

In June 1967, the Six-Day War between Israel, Egypt, Syria and Jordan took place. Following years of tensions, the Israeli Defence Forces launched airstrikes that crippled the air forces of Egypt and its allies. It then deployed a successful ground offensive and seized the Sinai Peninsula, the Golan Heights, the Gaza Strip, the West Bank and East Jerusalem, causing around 250,000people to flee.

© emmy·in·the·mix

Legal status

The influx of Palestinians to Jordan after the 1948 and 1967 wars resulted in the creation of several categories of refugees, with different legal statuses. Those who came in 1948 were granted Jordanian citizenship with full rights.

Those who came in 1967 were refugees from the Gaza Strip in Palestine (Gazans). Upon arrival, they were granted temporary Jordanian passports without citizenship rights. These refugees and their descendants are the ones living today in the Gaza camp in Jordan. They were either:

- people originating from Gaza who were displaced for the first time in 1967

- refugees from Palestinian villages and towns that became part of Israel in 1948 who fled first to the Gaza Strip, ruled by Egypt. After the 1967 war, they were displaced for a second time: as their Egyptian travel documents did not entitle them to enter Egypt, they fled to Jordan.

But what was supposed to be a temporary residence until the situation calmed down proved to be a permanent one: they are still not allowed to return to the Gaza Strip or to their homes and villages of origin. Today, they are neither citizens nor Jordanian nationals. Since according to international law, there is no Palestine state per se, those who have not had the chance to acquire the nationality of a third state, therefore, remain stateless.

It is possible to acquire citizenship through marriage, but only for Gazan women who marry Jordanian citizens. A Gazan man cannot benefit from the citizenship of his Jordanian wife. Another way to get Jordanian nationality is to make a USD 750,000 investment in SMEs in the country, a prohibitive amount for most of them.

Gaza refugees are one of the most vulnerable groups in Jordan. Their temporary Jordanian passport serves as ID, residency permit and international travel documents. Passports must be renewed every 2 or 5 years, which is costly and may be denied, notably if the person has travelled abroad or on the grounds of national security.

“Recently, we’ve been able to renew our temporary passport and personal ID for a duration of 2 or 5 years. A 2-year renewal costs JOD 100 (USD 141) and a 5-year renewal costs JOD 200 (USD 282)” says W., 26.

Consequences on daily life

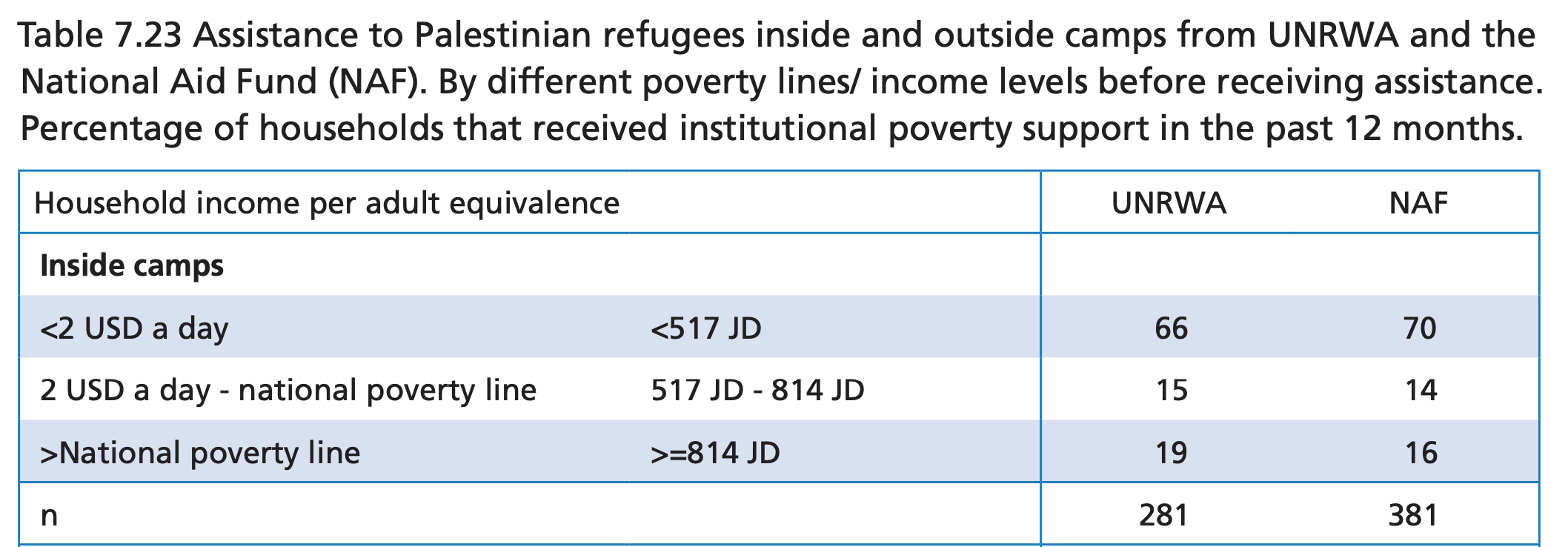

Not holding a national ID number limits their access and entitlement to education, employment, benefits and healthcare. It makes them much more likely to be poor, but also over 3 times as likely to be amongst the most destitute, living on less than USD 1.25 a day.

Source: Fafo report, 2013

Given their status, laws that are applicable to foreign nationals become applicable to them. Although they are provided with some aid, health and education services by the UNRWA, not all of their needs can be met. Here are some illustrations.

Administrative procedures

Gazans are not entitled to receive social, financial or housing support from the Jordanian state. They are denied the right to own property, whether land or building or car. To own it, they must register it in the name of a citizen or resident who is entitled to do so.

“We can buy a maximum of 2 petrol-powered cars, but not diesel ones, although they are cheaper” says W., 26.

Health

According to Fafo report, UNRWA is the dominant provider of primary healthcare in camps, providing virtually free preventive healthcare and limited curative medical treatment at its health centres. However, there are long waiting times and refugees indicate that private health clinics provide better services.

In Jerash camp, only 12% of residents have health insurance. This is due to their lack of citizenship which limits access to:

– government services, including government health insurance

– the labour market, and subsequent health insurance through their employer.

“Most people don’t have health insurance. Even people who work in special companies don’t have it. We need to pay double or triple for hospitals and clinics. Everything works with money.” says W., 26.

Whilst the Jordanian government has taken steps to improve the situation of Gazans, such as providing free health insurance to all children under 6, health insurance coverage amongst them remains low. In addition, the elderly are not allowed to be admitted in elderly caring centres.

Education

Primary, secondary education and vocational training are quite accessible. However, young Gazans who wish to enrol in university qualify as international students, who must pay much higher tuition fees. Paying the “Jordanian” fee requires applying to special agencies, for a limited number of seats and high competition. The same applies to scholarships.

“The cost of university is around JOD 8,500. We invest for the kids, not for a land.” says H., 57.

Politics

Gazans cannot vote, they are not represented in parliament and cannot register in any political party.

Work

Gazans, as holders of temporary passports and non-Jordanians, must apply for a work permit to work legally and thereafter have limited access or are excluded from certain sectors.

- Private sector: working there is contingent upon security approval. They are required to show that they have skills or qualifications not available in the Jordanian workforce. They are prohibited from practising several professions such as dentistry, engineering, certified accounting, and working in 4- and 5-star hotels.

“Workplaces in Jordan ask for “raqam watani” (editor’s note: the equivalent of a social security number) – if they don’t have it, they can’t work in most cases” says W., 26.

- Public sector employment is not available, which is a significant disadvantage as the government is considered the major employer in Jordan.

- If considering self-employment to establish private businesses outside the camp, they need special clearance from the government which is rarely granted, and there are state taxes to pay. They often lack the skills, licences and resources to start their own small business. They are not allowed to register with professional unions, to become members of cooperative associations, create their own offices, firms or clinics.

- The informal sector is an option but there is a risk of exploitation.

“Every regular family has 2-3 members without a job” says W., 26.

Travelling

For many Gazans, survival often means leaving Jordan to look for work. But their legal status restricts their mobility, for business and pleasure.

“Egypt is hard to go to, Turkey is easier. With our temporary Jordanian passports, we need a visa. For European countries, we have to apply to the embassy, pay the fee, with no guarantee that it will be approved” says W., 26.

Life inside the Gaza camp

What was originally an overcrowded camp with basic sanitation has improved over the last couple of decades. There has been progress across school enrolment, educational attainment and living conditions. Here is an overview of what it is like to live inside the Gaza camp.

Authority

The Department of Palestinian Affairs is present inside the camp and settles administrative matters. The UNRWA deals with social issues, but ultimately, it is the Jordanian and Palestinian agencies who have responsibility.

“Inside the camp there is no racism, and there is little coming from neighbouring towns as we have been living here for a long time” says W., 26.

Housing

The original shelters were prefabricated and provided by the UNRWA. Many of these have been replaced with more durable structures. Separate, proper kitchens, bathrooms and inside toilet are now the norm.

View from a rooftop. @waseem.salameh

Most people rent houses from owners who are either from inside or outside the camp. For Gazan homeowners, the lack of deeds to the land upon which it is erected means they cannot legally own it. The land is provided for free by the Jordanian government, which either owns the land or has long-term leasing agreements with private landowners.

“Three years ago, Jordanian landowners sued the UNRWA to increase rent from the land. The case is still ongoing.” says W, 26.

Infrastructure

Gaza camp was infamously known for its dire sanitation conditions, where sewage and wastewater were released through holes in the floors of refugees’ houses into a concrete maze, or dumped into ditches running under their homes, causing many health problems.

Since 2016, the camp’s 3,000 houses enjoy functioning water and sewage networks, thanks to a project funded and supported by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation.

“20 years ago, there was no cement on the streets. We used to have to queue to get gallons of water periodically from the UNRWA. The quantity depended on the size of the household. Today, every house has a meter to calculate water consumption, although they have leaks. We get invoices every 3 months from the Jordanian water company. Electricity is also provided by a Jordanian company, with some periodical cuts.” says A., 40.

Regarding waste management, rubbish used to be collected by the UNRWA three times a week. It then became less frequent and unreliable. Nowadays, rubbish is either dumped in the street or burnt.

A common means of transportation in the camp. @waseem.salameh

School

The UNRWA has been and still is the dominant provider of basic schooling in the camp.

“The UNRWA school was full of asbestos. It has now been renovated.” says A., 40.

“Teachers are good, but classes are too packed: there can be 40 to 45 students in one class. For one month there is a morning shift, and the next one is afternoon shift. Boys and girls are separated” says W., 26.

Society

Gaza camp is no stranger to patriarchal society. Marriage means different things for men and women. There is still a strong male breadwinning role in Arabic culture, which is associated with being responsible for one’s own family while for most women, it brings expectations of motherhood and responsibility over domestic work. However, married women do work: some of them (re-)enter employment after raising their children.

“There was social pressure to have a lot of kids. If I had awareness, I would not have had so many children, so I could take care of them better. Not having a sufficient gap in between children caused me health problems.” says A., 40.

Final words

Due to their lack of citizenship, Gazans are disproportionately disadvantaged compared to other Palestinians and ordinary Jordanian citizens. They have fewer rights and opportunities in life, with limited access to health, education, work and travel.

International programmes aimed at improving housing and sanitation in the camp have contributed to better living conditions over the past few years. However, in addition to legal status, a core issue remains access to employment, which prevents them from building a sustainable future. These limitations have already affected a few generations: anyone who is aged up to 54 years was born in the camp.

The absence of a political solution contributes to the permanence of their vulnerable living conditions and maintains them in a permanent temporality. They are and remain de facto refugees from a land they have never seen and cannot go back to. Ever?

Resources

-

Fafo 2013 report: https://www.unrwa.org/sites/default/files/insights_into_the_socio-economic_conditions_of_palestinian_refugees_in_jordan.pdf

-

PRC 2018 report:

-

https://prc.org.uk/upload/library/files/BreadReportJordan2018.pdf On restrictions:

-

On restrictions:

-

On life in the camp:

-

https://reliefweb.int/report/jordan/born-bred-without-rights-gaza-strip-refugees-jordan

-

How you can help: buy from a rare private company operating in the camp and creating employment for many women -->https://sepjordan.com/

*For confidentiality reasons, camp residents were quoted with an initial, followed by their age.

Copyright emmy·in·the·mix