The Keffiyeh Through The Ages: a feature story on GRAZIA Middle East

Posted on October 18 2024

Words: Maya Abuali

For a set of threads strung together on a loom, the keffiyeh has the potential to elicit a profound array of human emotions. Ask any local in the Levant, Saudi Arabia, or Iraq, and they might say it’s simply a time-honoured element of their customary dress. But to many others, it carries the weight of so much more.

The feelings a keffiyeh evokes — hope, strife, resistance, pride, dissent, or comfort — depends on the wearer and the moment. With perspectives from historians, culture experts, and designers, GRAZIA takes a closer look at the keffiyeh’s rich past and its multivalence.

For Roberta Ventura, the Italian-born founder of Social Enterprise Project (SEP) – which employs Palestinian and Jordanian refugee women to hand-embroider modern versions of keffiyehs – her enchantment with the garment began at an early age.

“Ever since I was a child traveling to North Africa and the Middle East, I was mesmerised by the keffiyeh, whether black and white or colourful,” Roberta tells GRAZIA. “I would go into a trance looking at it… even as a kid, without knowing the history, there was something so powerful about this scarf.”

The threads of the keffiyeh we see most commonly today are laden with symbolism: the intersecting straight lines trace ancient trade routes, with white standing for hope, black for strife. The fishnet pattern symbolises a connection to the sea, while the olive-leaf pattern honours the cultural ties to the olive tree. But these stories are a mere thread in a much older, more elusive tapestry that whose tendrils reach into ancient times.

Keffiyeh’s Origins: From Priestly Regalia to Desert Wear

Dating back to Sumerian priests in Mesopotamia around 1300 BCE, the keffiyeh (or hattah) once denoted honour and status. The word itself, derived from the city of Kufa in Iraq, translates to ‘from Kufa’, though the garment eventually wove itself into traditional attire throughout most of the Middle East. Initially donned by priests to signify their rank, the piece’s significance evolved as it spread across time and space, from priesthood to parochialism.

Over time, the keffiyeh was adopted by Bedouins and farmers as a pragmatic measure, shielding wearers from the desert’s harsh sand, wind, and dust. In form, it was generally a large square cloth draped over the head and secured with a black cord known as an ‘aqal’. Though ornamental today, the aqal served a practical function: when untied, it could be used to hobble a camel’s legs.

“It was and is used throughout the Middle East by everyone, including Muslims and Christians,” Dr. Bernard Haykel, a professor of Near Eastern studies at Princeton University, tells GRAZIA. “It’s become part of the national dress in some countries and comes in different colours and patterns.”

Before its black-and-white style became widely adopted, these colours and patterns varied with each region, reflecting local pride. Communities across the Middle East tailored the fabric – usually cotton, silk, or fine wool – to their needs and environment.

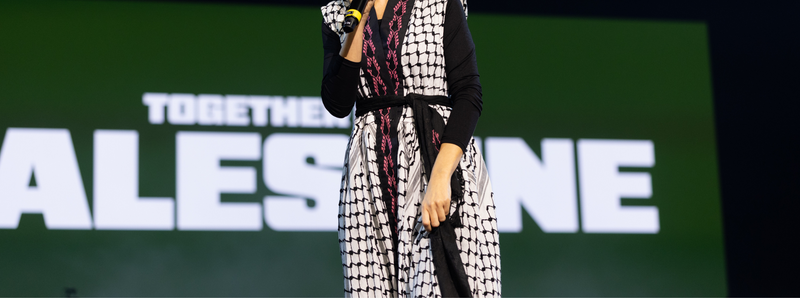

"Abroad, the ’60s gave way to the era of countercultural revolutions, and the keffiyeh began to crop up far beyond the borders of the Middle East, finding unexpected resonance in Western movements. In the hands (or on the heads) of anti-war activists of this period, the keffiyeh became a deliberate signifier of those fighting against all forms of imperialism and oppression.

“For young people, it’s a symbol of equality, freedom, and human rights,” Ventura explains. “It’s not just a struggle of one people; people wear it to show who they are. It’s a way of expressing what they believe in.”

Artists like Madonna and Pat Benatar, idols of rebellion in late 1970s and ’80s pop culture, began to use the keffiyeh as their own accessory of anti-authoritarian sentiment, separate from the garment’s native origins. This Western integration precipitated a new era for the keffiyeh’s understanding, one marked by appropriation rather than solidarity."